ObamaCare means rationing of health care services. Obama dodges and weaves on that, trying to avoid admitting that care will indeed be rationed.

He, of course, doesn’t want the public to understand what government-run health care would really entail.

At his alleged town hall meeting in Portsmouth, New Hampshire yesterday, (actually, it was more like a campaign rally), Obama extolled the wisdom of “expert health panels” and their role in government-run health care.

OBAMA: In terms of these expert health panels — well, this goes to the point about “death panels” — that’s what folks are calling them. The idea is actually pretty straightforward, which is if we’ve got a panel of experts, health experts, doctors, who can provide guidelines to doctors and patients about what procedures work best in what situations, and find ways to reduce, for example, the number of tests that people take — these aren’t going to be forced on people, but they will help guide how the delivery system works so that you are getting higher-quality care.

Obama touts the judgment of these “expert health panels.”

One such “health expert” is Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, a top adviser to Obama.

Ezekiel Emanuel has a system for determining how to allocate health services. (Allocating, in effect, is rationing.)

Emanuel promotes the “Complete Lives System” as a way to decide who gets treatment and who is denied.

From The Lancet, Volume 373, Issue 9661, Pages 423 – 431, 31 January 2009, Emanuel writes:

The complete lives system

Because none of the currently used systems satisfy all ethical requirements for just allocation, we propose an alternative: the complete lives system. This system incorporates five principles: youngest-first, prognosis, save the most lives, lottery, and instrumental value. As such, it prioritises younger people who have not yet lived a complete life and will be unlikely to do so without aid. Many thinkers have accepted complete lives as the appropriate focus of distributive justice: “individual human lives, rather than individual experiences, [are] the units over which any distributive principle should operate.” Although there are important differences between these thinkers, they share a core commitment to consider entire lives rather than events or episodes, which is also the defining feature of the complete lives system.

Consideration of the importance of complete lives also supports modifying the youngest-first principle by prioritising adolescents and young adults over infants. Adolescents have received substantial education and parental care, investments that will be wasted without a complete life. Infants, by contrast, have not yet received these investments. Similarly, adolescence brings with it a developed personality capable of forming and valuing long-term plans whose fulfilment requires a complete life. As the legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin argues, “It is terrible when an infant dies, but worse, most people think, when a three-year-old child dies and worse still when an adolescent does”; this argument is supported by empirical surveys. Importantly, the prioritisation of adolescents and young adults considers the social and personal investment that people are morally entitled to have received at a particular age, rather than accepting the results of an unjust status quo. Consequently, poor adolescents should be treated the same as wealthy ones, even though they may have received less investment owing to social injustice.

The complete lives system also considers prognosis, since its aim is to achieve complete lives. A young person with a poor prognosis has had few life-years but lacks the potential to live a complete life. Considering prognosis forestalls the concern that disproportionately large amounts of resources will be directed to young people with poor prognoses. When the worst-off can benefit only slightly while better-off people could benefit greatly, allocating to the better-off is often justifiable. Some small benefits, such as a few weeks of life, might also be intrinsically insignificant when compared with large benefits.

Saving the most lives is also included in this system because enabling more people to live complete lives is better than enabling fewer. In a public health emergency, instrumental value could also be included to enable more people to live complete lives. Lotteries could be used when making choices between roughly equal recipients, and also potentially to ensure that no individual—irrespective of age or prognosis—is seen as beyond saving. Thus, the complete lives system is complete in another way: it incorporates each morally relevant simple principle.

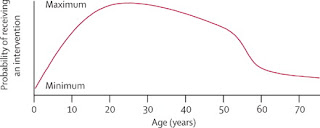

When implemented, the complete lives system produces a priority curve on which individuals aged between roughly 15 and 40 years get the most substantial chance, whereas the youngest and oldest people get chances that are attenuated. It therefore superficially resembles the proposal made by DALY advocates; however, the complete lives system justifies preference to younger people because of priority to the worst-off rather than instrumental value. Additionally, the complete lives system assumes that, although life-years are equally valuable to all, justice requires the fair distribution of them. Conversely, DALY allocation treats life-years given to elderly or disabled people as objectively less valuable.

Finally, the complete lives system is least vulnerable to corruption. Age can be established quickly and accurately from identity documents. Prognosis allocation encourages physicians to improve patients’ health, unlike the perverse incentives to sicken patients or misrepresent health that the sickest-first allocation creates.

Objections

We consider several important objections to the complete lives system.

The complete lives system discriminates against older people. Age-based allocation is ageism. Unlike allocation by sex or race, allocation by age is not invidious discrimination; every person lives through different life stages rather than being a single age. Even if 25-year-olds receive priority over 65-year-olds, everyone who is 65 years now was previously 25 years. Treating 65-year-olds differently because of stereotypes or falsehoods would be ageist; treating them differently because they have already had more life-years is not.Age, like income, is a “non-medical criterion” inappropriate for allocation of medical resources. In contrast to income, a complete life is a health outcome. Long-term survival and life expectancy at birth are key health-care outcome variables. Delaying the age at onset of a disease is desirable.

The complete lives system is insensitive to international differences in typical lifespan. Although broad consensus favours adolescents over very young infants, and young adults over the very elderly people, implementation can reasonably differ between, even within, nation-states. Some people believe that a complete life is a universal limit founded in natural human capacities, which everyone should accept even without scarcity. By contrast, the complete lives system requires only that citizens see a complete life, however defined, as an important good, and accept that fairness gives those short of a complete life stronger claims to scarce life-saving resources.

Principles must be ordered lexically: less important principles should come into play only when more important ones are fulfilled. Rawls himself agreed that lexical priority was inappropriate when distributing specific resources in society, though appropriate for ordering the principles of basic social justice that shape the distribution of basic rights, opportunities, and income.1 As an alternative, balancing priority to the worst-off against maximising benefits has won wide support in discussions of allocative local justice. As Amartya Sen argues, justice “does not specify how much more is to be given to the deprived person, but merely that he should receive more”.

Accepting the complete lives system for health care as a whole would be premature. We must first reduce waste and increase spending. The complete lives system explicitly rejects waste and corruption, such as multiple listing for transplantation. Although it may be applicable more generally, the complete lives system has been developed to justly allocate persistently scarce life-saving interventions. Hearts for transplant and influenza vaccines, unlike money, cannot be replaced or diverted to non-health goals; denying a heart to one person makes it available to another. Ultimately, the complete lives system does not create “classes of Untermenschen whose lives and well being are deemed not worth spending money on”, but rather empowers us to decide fairly whom to save when genuine scarcity makes saving everyone impossible.

Legitimacy

As well as recognising morally relevant values, an allocation system must be legitimate. Legitimacy requires that people see the allocation system as just and accept actual allocations as fair. Consequently, allocation systems must be publicly understandable, accessible, and subject to public discussion and revision. They must also resist corruption, since easy corruptibility undermines the public trust on which legitimacy depends. Some systems, like the UNOS points systems or QALY systems, may fail this test, because they are difficult to understand, easily corrupted, or closed to public revision. Systems that intentionally conceal their allocative principles to avoid public complaints might also fail the test.Although procedural fairness is necessary for legitimacy, it is unable to ensure the justice of allocation decisions on its own. Although fair procedures are important, substantive, morally relevant values and principles are indispensable for just allocation.

Conclusion

Ultimately, none of the eight simple principles recognise all morally relevant values, and some recognise irrelevant values. QALY and DALY multiprinciple systems neglect the importance of fair distribution. UNOS points systems attempt to address distributive justice, but recognise morally irrelevant values and are vulnerable to corruption. By contrast, the complete lives system combines four morally relevant principles: youngest-first, prognosis, lottery, and saving the most lives. In pandemic situations, it also allocates scarce interventions to people instrumental in realising these four principles. Importantly, it is not an algorithm, but a framework that expresses widely affirmed values: priority to the worst-off, maximising benefits, and treating people equally. To achieve a just allocation of scarce medical interventions, society must embrace the challenge of implementing a coherent multiprinciple framework rather than relying on simple principles or retreating to the status quo.

Age-based priority for receiving scarce medical interventions under the complete lives system

Emanuel, WHITE HOUSE HEALTH CARE POLICY ADVISER, has some very scary ideas about who’s fit to live and who’s life has been full enough.

Look at the chart. Determining whether to permit medical intervention on a curve?

Should older Americans be concerned about this? I think so. The very young are also targeted.

At his event in Portsmouth yesterday, Obama tried to convince Americans that rationing won’t occur under his single payer plan.

But we’ve seen how socialized medicine works. It doesn’t raise the standards of care for everyone. It creates scarcity. Quality care? Forget it.

Obama mocked opponents who point out that a government-run health care system bent on trimming expenses will mean cutting services.

OBAMA: Let me just be specific about some things that I’ve been hearing lately that we just need to dispose of here. The rumor that’s been circulating a lot lately is this idea that somehow the House of Representatives voted for “death panels” that will basically pull the plug on grandma because we’ve decided that we don’t — it’s too expensive to let her live anymore. And there are various — there are some variations on this theme.

The Complete Lives System does “pull the plug on grandma.”

Emanuel is an “expert” Obama admires.

As Obama said in Portsmouth, “[W]e’ve got a panel of experts, health experts, doctors, who can provide guidelines to doctors and patients about what procedures work best in what situations.”

These same experts also will provide guidelines to doctors about what procedures will not be allowed.

Remember what Obama said on ABC during his health care infomercial in response to this question from Jane Sturm:

OBAMA: We’re not going to solve every difficult problem in terms of end-of-life care. A lot of that is going to have to be we as a culture and as a society starting to make better decisions within our own families and for ourselves.

But what we can do is make sure that at least some of the waste that exists in the system, that’s not making anybody’s mom better, that is loading up on additional tests or additional drugs, that the evidence shows is not necessarily going to improve care, that at least we can let doctors know, and your mom know, that you know what, maybe this isn’t going to help. Maybe you’re better off not having the surgery but taking the painkiller.

If the “expert health panel” deems certain treatments not cost effective, the government will be pulling the plug on “grandma.”

_________________